I’m excited to announce a new collaborative project with my friend, John Powers, called “2H2K”. 2H2K brings together our shared interests in science fiction, urbanism, futurism, cinema, and visual effects into a multimedia art project that imagines what life could be like in the second half of the 21st century.

We’ve structured the project to proceed as if we were developing and doing the pre-production for an imagined sci-fi movie. We’re using fiction, drawing, sculpture, collage, comics, conversation, technical research, speculative design, and interactive technology to explore the cultural and human effects of the big changes coming to our world in the 21st century. As John set out in his introduction to the project, these changes include slowing population growth, mass migration of people into cities, and technological transformations in the value and organization of labor.

John and I have been discussing the project and working on it in preliminary forms for the past six months. This week, John began posting the first of the planned 12 short stories he’s writing to kick us off. They’re organized around each of the twelve months of the year 2050. Read the first three here (along with John’s introductions to them):

- 2H2K – January 2050: LoaneRs

- 2H2K – February 2050: The Slab (John’s introduction)

- 2H2K – March 2050: WildcRaft (John’s introduction)

In this post, I’ll provide some background on my own interests that lead me to the project, how I came to approach John about it, and some of the areas that I’ve been thinking about so far.

From Star Wars to Jedi

My earliest memory of television comes from when I was three. The image turns out to be part of From Star Wars to Jedi: The Making of a Saga, a television documentary that aired in the manic run-up to the release of Return of the Jedi.

The memory starts with a shot from Empire. It’s a shot of an Imperial Walker in the snow. Everything about the shot looks perfect, just like the movie. The Walker is frozen mid-stride on a snowy plain in front of far away jagged hills under a pale sky of puffy clouds. And then, suddenly, a huge man emerges from beneath the horizon. He’s bigger than the Walker. Much bigger. He dwarfs it. After a moment’s consideration he reaches in to adjust it.

Something about this image hit me hard. In remembering it since two ideas have wrapped themselves around the memory. The first one is about scale. The magical transporting images of these movies were made out of stuff. Small stuff. Bits of real things that were made and manipulated by people. They’d formed these bits into a model of another world that they could look down into and change and work.

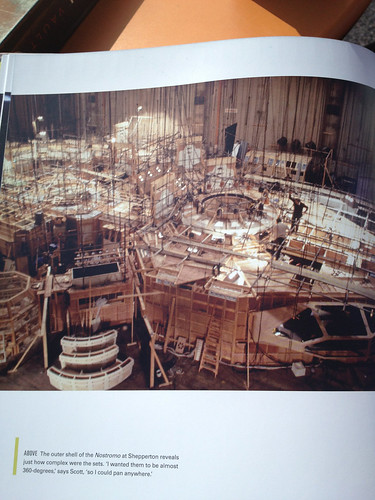

The second idea was about people. My god, this was someone’s job! To get in there amongst the stuff and get your hands on it. They got to live in these unfinished worlds with all their raw edges. They got to see them while they were still part of the real world, before the camera came in with its mercilessly abstracting rectangle and hid all the supports and jigs and armatures and mechanisms, leaving just a stump, dead and ready for display.

The man in that image, of course, was Phil Tippet, the brilliant stop motion artist responsible for much of the magic in the original trilogy. His job, it turned out, was called “visual effects”. That moment kicked off a life-long love of visual effects for me – a love not just of the effects the field could achieve, but of that always fragmentary world of objects, of all of those supports and mechanisms, that lay behind it.

More even than visual effects movies themselves, I love the artifacts of them behind-the-scenes and in-progress: plates with partially-rendered creatures, bits of sets bristling with equipment, un-chromakeyed green screen, etc. This is “world building” not just as an act of imagination, but as the palpable pushing of atoms and bits.

Approaching John

With this start (and an early adulthood that included constant reading of science fiction, an art education studying under an unclassifiable post-minimalist painter, and a spate covering urban planning in Portland), I may have been the single perfect reader for John Powers’ essay, Star Wars: A New Heap. The piece hit me like a lightning bolt. It combined the politics of urbanism, the philosophy of minimalist art, and the material texture of Star Wars’ visual effects into a coherent aesthetic and political world view. For me, it provided the unique pleasure only available when the external world conspires to combine multiple of your own seemingly disparate interests in a way that reveals their interrelations. John, via Robert Smithson, had put a name on what drew me to behind-the-scenes images: the power of the “discrete stage”.

When I moved to New York years later, I sought John out and we became friends. Earlier this year I came to him with a proposal for a collaborative project. I’d been thinking about one of the challenges of a discrete stage/behind-the-scenes aesthetic: you need a final artifact to head towards, a show who’s scenes you can be behind.

In searching for a sci-fi story to tell, I’d struck on an image: one of John’s sculptures, scaled up to the size of a building and towering over the New York skyline (as in the collage at the top of this section). Once I imagined it, my head started filling up with questions. Was it a building? If so what had happened to the world that had pushed architecture to such radical extremes? What if it wasn’t a building? What other kind of technological process or cultural entity could have made it and for what purpose? Was it even physical? What if it wasn’t present at all, but some kind of Modernist augmented reality fantasy meant to spice up a post-Thingpunk world?

I didn’t have answers to these questions, but they felt like speculations that could generate stories so I decided to bring the idea to John. I showed him the image and asked him: what would make the world like this?

John had already shown himself to be a handy (re)writer of science fiction with his re-invention of the unfortunate Ridley Scott Alien prequel, Prometheus (re)Bound. And we’d had some really interesting conversations about technology and aesthetics at Robotlife a meetup organized by Joanne McNeil and Molly Steenson in response to the New Aesthetic.

We started the process with a few wide-ranging conversations about the future. We talked about climate change, population growth, the explosion of cities, changes in the lives of artists, the future of technologies like cameras, 3D printing, robotics, and artificial intelligence. As John set off to write stories, I started bringing together background research, design speculation, drawings, and sketches. I found myself imagining the future through sketches for products, imagined Wikipedia articles, and dreams of images made by impossible cameras. As the project continues I’ll be posting artifacts of those in the forms of drawings, 3D models, comics, collages, prototypes, etc.

These artifacts will sometimes illustrate John’s stories, sometimes explore ideas from our conversations that didn’t make it into them directly, and sometimes expand our imagined future beyond them. They’re an attempt to do science fiction with objects, images, text, and code.