The US venture capital industry is a transient epiphenomenon built upon the greatest bull market in the history of capitalism.

— William Janeway, Warburg Pincus

The venture capital industry underwent an epochal expansion around the year 2000 in the wake of the internet boom. In response to the incredible success of web companies, the amount of money invested in VC funds increased ten-fold before falling rapidly back to pre-boom levels after the crash.1

The result was a decade in which an unprecedented quantity of capital was available to technology entrepreneurs as venture capitalists invested the money raised during the boom. This period has now come to an end. Startups in the next ten years will have an order of magnitude less money available to them during the early stages of their development. This change will have dramatic effects on the kinds of opportunities available to entrepreneurs and technologists and on the kinds of change effected by the products they develop.

The History and Structure of Venture Capital Firms

Since its advent in the late 40s2, the venture capital industry has provided essential support to companies developing and commercializing new technology. Venture firms provide capital to startup businesses lacking access to traditional bank loans due to the unproven or risky nature of their enterprise. VCs played a central role in developing and scaling up many important technologies in the 20th century from the semiconductor to the personal computer and the web.3

The size of the industry grew dramatically in the 80s and 90s. During the PC boom in the 80s the amount of money VC firms had under management grew from $3 billion to $31 billion dollars and the number of operating firms shot up to 650.4 This expansion then accelerated during the late 90s dot com bubble when, in 2000, VCs raised nearly the previous total holdings of the industry in each quarter, spiking the total funds up to $230 billion in just a few years.5

Quarterly venture capital investment data courtesy of the National Venture Capital Association

After 2000, fundraising returned to pre-boom levels with around $9 billion raised so far in 2010.6

In other words, in both the 80s and 90s, the great body of venture capital investment acted as a trailing indicator of technical innovation — first following opportunity in personal computers after its early successes had become obvious and then doing likewise with the web.

Most venture capital funds are structured as private partnerships with a fixed term of seven to ten years.7 Funds spend the first half of their terms selecting companies for investment and the second half shepherding their companies through “liquidity events”, acquisitions or Initial Public Offerings which end the ownership of the company by the fund and provide the investors with a return on their money.

The combination of this sudden spike in dollars invested and this fixed-term structure resulted in a unique decade-long period in which a lump of cash on the order of $200 billion worked its way through the startup ecosystem. Much of our conventional wisdom about the culture and economics of startups are based on these conditions and are unlikely to hold up well outside of them.

The Last Ten Years: No Exit

In addition to a surplus of venture capital funding there were three other major economic factors shaping the startup ecosystem in the last decade: the significantly lower cost of starting an online business, the weakness of the Initial Public Offering market, and the flight of institutional investors to other more attractive forms of high risk capital. Together they formed a kind of Bermuda Triangle for the VC industry: many entered, but few who did were ever seen again.

During the web boom both hardware and software costs were high for nascent startups. Web server software was mostly proprietary and hence involved large licensing fees. For example in 1995, a single license for Windows NT Server 3.5 cost $1,495.8 Worse still, typical server hardware for running this operating system would have cost around $15,500.9

Today, open source software, cheap, extremely capacious commodity hardware, and the use of “cloud computing” services such as Amazon Web Services have driven both software and hardware costs down substantially,10 a situation which reached a notable data point recently when Amazon announced a free pricing tier for its EC2 service. This lowering of costs has reduced startups’ demand for venture capital. Since it no longer takes millions of dollars up front to start a web company, founders are less motivated to sell off equity in exchange for funding.

On the other side of the equation, venture funds found fewer opportunities to profitably exit from their investments. In the 80s and 90s VCs had two exit strategies: acquisition by existing large companies and the issuing of public stock. Due to a murky combination of factors including increased regulation of publicly owned companies enacted by Sarbanes-Oxley in 200211, the number of venture-backed technology IPOs was down precipitously in the past decade. Between 1995 and 2000 the market averaged 204.5 IPOs per year while the next seven years saw an average of just 49.12

Taken together, these two factors meant a large decrease in profit-making for Venture Capital firms, down from 85% return on investment for an average firm during the bubble years to -3% in the last five.13 This catastrophic drop-off has caused venture firms to issue far fewer funds and some firms to close altogether.14

And, to make the situation even worse for VC firms, institutional investors have begun withdrawing their vast sums under management from the VC industry. During the 80s and 90s these investors gradually increased their investment in VC contributing significantly to the build-up of VC funds. But after the crash of 2008 made them decidedly more risk averse, they have fled for safer options.15

What About Biotech?

One objection to this rather bleak portrait of the prospects for venture capital might be to argue that the problem is constrained to the web. A case might be made that the web has reached maturity as a technology and hence no longer needs VC investment to develop or scale its technology and so we should look for bright spots for venture investors in other sectors.

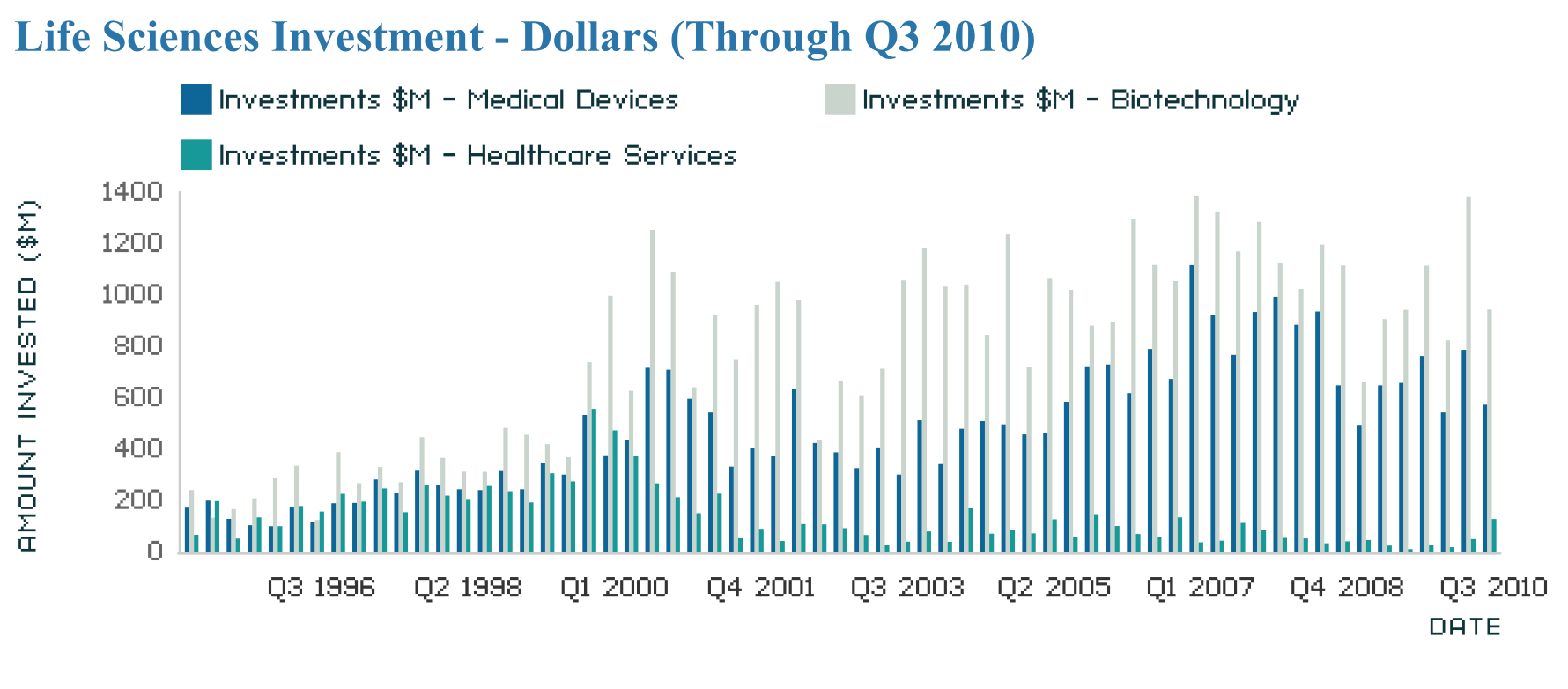

A prime candidate for such a sector would be biotechnology. And VC investment in biotechnology has increased since 2000 both as an absolute number and as a portion of total VC funds, growing from a mere 7.5% in 2000 to 34.6% in 2009.16

Life Sciences Investment data courtesy of the National Venture Capital Association

However, there are reasons to doubt venture capital’s effectiveness in supporting biotechnology. William Janeway, a Managing Director and Senior Advisor at venture firm Warburg Pincus has argued that the long time it takes for life science innovations to progress from lab to clinic combined with the high rate of attrition and the lack of positive cash flow for early investors makes the biotech sector a tough environment for venture capitalists.17 Further the seeming profitability of the industry seems to have been artificially buoyed by the presence of a single highly profitable company: “if we take the largest and most profitable firm Amgen, out of the sample the industry has sustained heavy losses throughout its history.”18

Finally, counterintuitively, the prospects for profitability by biotech startups may actually be getting worse over time. “The field gets more complicated every year (from the Central Dogma, to Epigenetics, to Systems Biology),” Janeway says. “The big winners in BioTech came from the synthetic production in bacteria of naturally occurring proteins (insulin, human growth hormone) whose function had evolved over millions of years; the effort to produce truly novel therapeutics (e.g., fragments of protein) has been radically less productive. This suggests that it will get harder, not easier to make money in Biotech.”19

Conclusion

The state of the venture capital industry affects the kinds of startups that get founded and, through them, the types of jobs that are available in technology-related industries as well as the kinds of technologies that reach scale and affect our daily lives. In the 80s, when venture capital supported the personal computer industry, the jobs were at Microsoft, Apple, and Dell doing hardware and operating systems engineering. In the 90s, when VC supported the web, the jobs were at Amazon and Ebay and short-lived very well-funded flashes in the pan like Pets.com. They mainly encompassed server programming. In the last decade, VC massively supported social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr. Most of the jobs at those companies were in still softer fields such as customer support, design, and marketing. In many ways these startups are more like media companies than the technology companies of the past.

What will the startups that thrive in the low-VC environment of the next decade look like? What will it feel like to work for web companies that bootstrap their own growth through revenue rather than taking big investment up front? Which technologies will fail to achieve wide adoption for lack availability of big up front investment? Will another non-web industry come along and initiate a new boom and another trailing order-of-magnitude growth in VC investment?

Only time will tell.

Notes

- Based on quarterly fundraising data gathered by the National Venture Capital Association. The data is available interactively on the NVCA website. [back]

- Georges Doriot founded the first venture firm, American Research and Development Corporation, in 1946. The firm’s greatest success was Digital Equipment Corporation, a leader in the development of the minicomputer. Spencer Ante, Creative Capital: Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital, Harvard Business School Press, 2008. [back]

- Legendary silicon valley firm Venrock Capital alone invested in Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel, and Apple. See the Venrock company timeline. Similarly Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers supported many of the most important web companies from Netscape to Google. Kleiner Perkins Caufield and Byers portolio. [back]

-

Andrew Pollack, “Venture Capital Loses Its Vigor”,

The New York Times, October 8, 1989. [back] -

The total numbers under holding come from NVCA data sent to me via email by William Janeway, Managing Director and Senior Advisor at Warburg Pincus. [back]

-

ibid [back]

- Jennifer A. Post, “An overview of US venture capital funds”, Alt Assets, 2001. [back]

-

Jason Pontin,”Windows NT starts to pick up steam” InfoWorld. January 30, 1995 [back]

-

When InfoWorld ran a web server comparison test in April of 1996, they used “a Compaq 1500/5133 Prliant with two 133-MHz Pentiums, 6GB of storage, 128MB of RAM and two Netflex 3P network interface cards” for their NT tests, a system which clocked in at $15,569 and was still less expensive than its Sun/Unix equivalent which cost $22,995. “Are You Being Served?” InfoWorld. April 8, 1996 [back]

-

Guy Kawaski, “By the Numbers: How I built a Web 2.0, User-Generated Content, Citizen Journalism, Long-Tail, Social Media Site for $12,107.09”,

blog.guykawaskai.com.June 03, 2007 [back] - Opinions differ on the effect of “SOX” on the IPO market. See Amy Feldman, “What Does Sarbanes-Oxley Mean for Companies That Want to Go Public?”, Inc. September 1, 2005. for pro and Lynn Stephens and Robert G. Schwartz “The Chilling Effect of SARBANES-OXLEY: Myth or Reality?” The CPA Journal. June 2006. for con. [back]

-

Jay Ritter, IPO Data. Venture Expert, Thomson Financial. [back]

-

Data sent to me via email by William Janeway of Warburg Pincus. [back]

-

ibid. Pincus’s numbers place the number of funds issued at 653 in 2000 and 124 in 2010 for a decline of 94%. [back]

-

Udayan Gupta “Why Institutional Investors Are Turning Down Venture Funds”, Institutional Investor. September 21, 2010. [back]

-

Data sent to me via email by William Janeway of Warburg Pincus [back] -

Email conversation with the author. [back] -

Gary P. Pisano, “Science Business”, HBS Press. 2006. p.117 [back]

-

Email conversation with the author. [back]