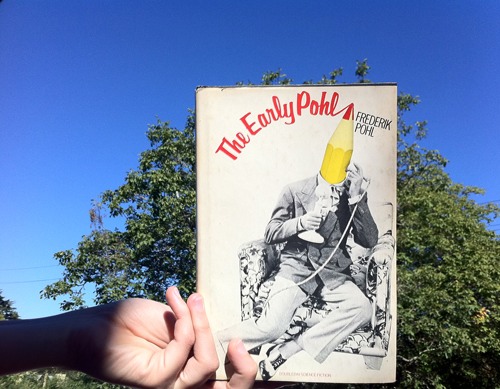

Frederik Pohl is a lesser Grand Master. Lifelong nerd, proto-fanboy, editor of old-timey pulp rags, union president, he is one of those eminently readable, largely innocuous fiction writers who has slogged his way into the canon via sheer persistence. I love Pohl, who has a beautiful imagination and a craftsman’s sense of story, but he is to folks like Heinlein and Clarke as a banana-flavored Mamba is to the fruit on the tree: delicious, but not quite the real thing.

Still, no tour of the space canon is complete without due diligence paid to the originals. And Pohl is an original, a founding father. Know your history, readers!

The Early Pohl is pleasantness embodied, a total comedown from my recent brush with the lunatic fringes. Pohl tells of his youngster’s love of science fiction, his work with the first glimmers of organized fandom, and his early career shilling and editing paperback pulp for a dime. He started the game young, editing two different science fiction magazines before he was twenty and heading up the local fanclub chapters like a champ. The Early Pohl is full of adorable details about what it was like to be a nerd before the word “nerd” existed: Cyril Kornbluth making cheap brandy with a homemade distiller in the bathroom of their shared house, putting together mimeographed fan mags, and hanging out at a soda fountain after the basement meetings of the Brooklyn Science Fiction League so much that the place named a sundae after them. Pohl lovingly recalls his involvement with the Futurians, a New York-based fan group that nurtured the careers of Kornbluth, Damon Knight, Hannes Bok, and Isaac Asimov, and their fierce competition with other fan groups for regional prominence.

Interspersed between these yarns — which detail his life from birth to just about after the war — are Pohl’s earliest stories, written in the late 1930s and early 40s for magazines like Amazing Stories, Astonishing Stories, and Planet Stories. They have scintillating titles like “Conspiracy on Callisto” and “Highwayman of the Void,” and march along diligently through picaresque tableaus with rough-around-the-edges/hearts o’ gold spacemen riding to neatly-wound conclusions. Still, they are clever and represent the pinnacle of genre at the time.

Of the glory days, Pohl writes:

“Science fiction was purely a pulp category in those days…I learned how to invent ray-guns and how to make a story march, but it was not for a long, long time that I began to try to learn how to use a story to say something that needed saying.

In fact, when I look back at the science-fiction magazines of the twenties and early thirties, the ones that hooked me on sf, I sometimes wonder just what it was we all found in them to shape our lives around. I think there were two things. One is that science fiction was a way out of a bad place; the other, that it was a window on a better one.”

Pohl’s early career unfolded over the background of the Great Depression and the Second World War, a climate of unimaginable fear and uncertainty. Yes, the science fiction of that era was glorified kiddie tales, but it hadn’t yet learned to pick up on the gloomy aspects of progress — to Pohl’s generation, science represented the potential for escape from the disaster of economic failure and war. No one was looking for a downside; they only saw the virgin capacities of uncolonized planets, and dreamt of a people united in the betterment of the species through new technology. “In those early days,” Pohl writes, “we were as innocent as physicists, popes and presidents. We saw only the promise, not the threat.” Incidentally, it’s telling of my own generational bias that the phrase “popes and presidents” inspires a completely opposite sentiment in my breast.

It’s fascinating to read about the actual birth of the thing. When Pohl was 13, science fiction as a popular genre was completely new; he helped construct its development, inventing its tropes, designing the first glimpses of alien civilization and rocket whiz-banggery. He and his friends took the structure of other pulp serials and applied layers of otherworldliness to it, changing the cowboys to cosmonauts, the untilled frontier to barren asteroids. Everything that came afterwards — from the golden age to the new-wavers, from the cyberpunks to the steampunks — issues from this genesis.

I find it beautiful and sad to read the evolution of science fiction from an essentially optimistic, escapist occupation into the primary expression for modern anomie. The more modern it is, the more it tends to be dystopian, or at least frank in its appraisal of technology’s complications and implications. In Pohl’s heyday, the future seemed unfettered and far off, a glamorous Valhalla for the warriors of efficiency. As the future catches up to us, and as we live with the consequences of the previous generation’s blind march towards progress, we just can’t feel that way anymore. Still, it only goes to show both the value and flexibility of science fiction that it can still feel relevant today despite what appears to be a complete reversal of its function.

From the Archives:

Space Canon review of Pohl’s JEM (in limerick, haiku, and sonnet format)

Space Canon review of Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson’s The Reefs of Space

Space Canon review of Frederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth’s Search The Sky

Bonus: Frederik Pohl’s first ever published work, a poem called Elegy to a Dead Planet: Luna