The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde is a 1970 collection of short stories by Norman Spinrad — syndicalist, anarchist, and active Internet user.

I had the same feeling reading The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde as I did when I read Bradbury as a kid, breathlessly tearing towards each story’s conclusion, eager to discover the clincher. At the outset, Spinrad seemed to combine the lucid dreaming of New-Wave science fiction with a more classical magazine-writing approach to story structure, something like Frederik Pohl explaining an LSD trip. Is it high art? Who cares? I just want to find out what’s inside the mysterious alien dome! After some meditation, however, I’ve found Spinrad to be a New Waver as hard-core as they come.

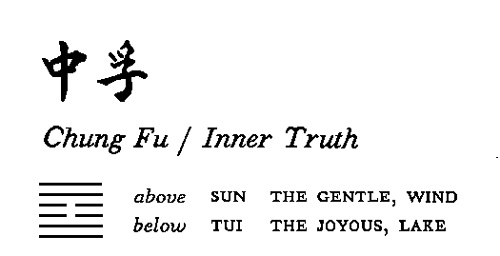

The most mind-expanding story in the collection is “Neutral Ground,” which manages to confound inner and outer space into a single unexplored entity. The story is about “Voyagers,” lab rats in a series of clinical studies testing a mysterious new drug called Psychion-36. Psychion-36 takes users to a place — a real Place. Though their bodies lie prone on psychiatric couches, the Voyagers most certainly travel to complex and detailed landscapes which seem like other worlds. Furthermore, multiple Voyagers visit the same places:

While their bodies lay in trances lasting for about an hour, their minds wandered through fantastic landscapes. And what was different about these hallucinations, what had made Project Voyage imperative, was that, although no Voyager had yet visited the same Place twice, there was strong evidence that different Voyagers had been to the same Places.

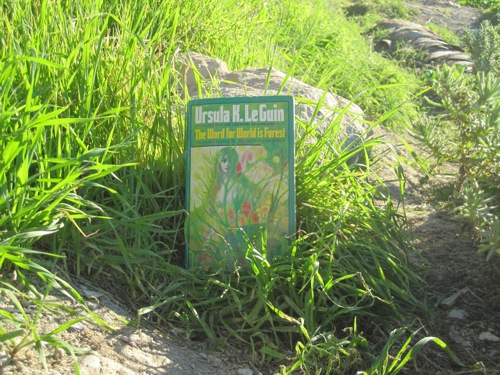

The Voyagers eventually encounter a non-human intelligence in their travels through the Places, and it proves to be a very different kind of “First Contact” than anyone could have expected. A great premise. Unfortunately, Spinrad, in this collection, is almost as much about what he doesn’t do with these perfect scenarios as what he does; “Neutral Ground” is a great story, but it’s not what, say, Le Guin or Tiptree might have done with it.

Spinrad, Harlan Ellison, and Robert Sheckley mugging at the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society in 1982.

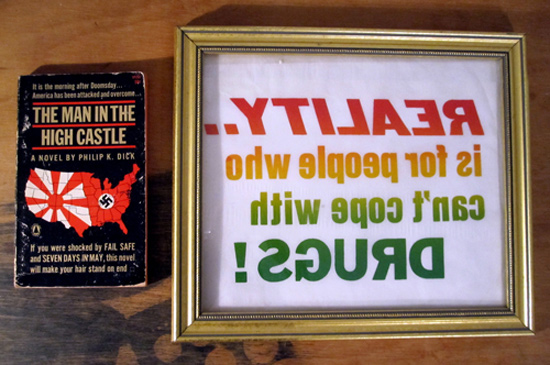

Many of the stories in Last Hurrah play with this nuance between inner and outer space, and the physicality of the mind. In the opening story, “Carcinoma Angels,” a man uses a potent cocktail of consciousness-expanding drugs to travel inside of his own body, Fantastic Voyage-style, and battle off his own illness. In “Subjectivity,” a crew of long-distance space travelers dosed with an experimental psychedelic to stave off the loneliness of their sixteen-year intergalactic journey manage to externalize and maintain their hallucinations deftly enough to live inside of them. In “A Child of Mind,” marooned astronauts encounter an organism that can make real their most specific fantasy of a mate. The mind, in Spinrad’s work, is the ultimate science-fiction apparatus. Not the engineer’s mind, the kind of mind that (as Bruce Sterling writes) is “interested in the transcendent poetics of a device per se,” in sublimation through the conduit of an external machine. There are objects of human ingenuity in these stories — spacecraft, faster-than-light drives — but they are cold, dead things. They’re furniture. The real fire is metaphysical; the mind that Spinrad evokes is the mind of the mystic, the hovering yogi, the telepath, the meta-programmable mind of John C. Lilly — the mind without limits.

It’s an interesting — maybe I’m reading too much into this — externalization of the act of science fiction. In Spinrad’s 70s heyday, the only machine used to make fiction was a typewriter. And the typewriter has as much to do with the final work as a hammer does to a nail: which is to say, it’s necessary, it can color the work inasmuch as the heaviness of a hammer might affect the force of a carpenter’s thrust, but it’s not like a nail won’t go into the wall if you slam it with a rock. Ideas come from the writer, not from his or her tools. So why would a piece of fiction play by different rules?

You could define the “Golden Age” of science fiction as being primarily phallo-centric, machine-lusting, tool literature: steam-powered metal men, Tom Swift and his Photo-Telescope, etcetera. This is just the DNA of the genre: pulp magazines were written to adolescent boys, and with Hugo Gernsback publishing the first “scientifiction” serials in Modern Electrics, science fiction literally emerged from a culture of machismo mechanical tinkering. The New Wave of the 1960s (of which Spinrad was at the heart) aimed to move beyond that stigma, and so a radical break from object fetishism played a large part.

Spinrad’s stories, so concerned with the science-fictional power of the mind, speak to the metaphysics of writer and type-writer, hammer and nail. Every time a character in The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde employs a Golden-Age “how does this doo-hickey work?” mentality, they are soundly rebuked. Spinrad clearly finds this way of thinking perverse and dated — he is for the transubstantiation of ideas into things, not of things into ideas. Success and failure, utopia and dystopia, all issue forth directly from the mind. In a great story called “Rules of the Road,” a character learns that space travel is a mental pursuit:

He felt a strangeness in his mind, a complexity beyond complexity, a revelation of new and unexpected textures in his psyche. Time was flux, space was flux, eternity was a variable…He did something with his mind, and the surface of the planet vanished like mist.

And then he stood up from the typewriter, and the ideas went with him.