Zberg Lament Exclusive

These are the days my friends, and these are the days my friends,

I write to you from six in the morning. I sleep on the couch for a week out of every month due to my night sweats, and it is odd to roll out of my dank sleeping bag and step directly into my coffee zone, but I’m not complaining (I complain ceaselessly).

Guess what? Readers of this Lament are hereby granted an EXCLUSIVE (or ‘sclusie, as Scott Aukerman calls them), not yet made public to the general readers of my blog. This ‘sclusie is as follows: …

PUBLISHER INTERRUPTION

Did you know that Zuckerberg’s Lament is also a monthly email? Well, it is. And normally we’ll send you just the intro to each of our wonderful articles and have you read the article on the web, but this month, in light of our POWERFUL EXCLUSIVE, we’re actually publishing the entire Letter From The Editor only in the email.

It’s April 4th right now and we’ll be sending out the email on April 5th, so…

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP NOW

Period.app

As we all know, one of the only advantages in being a woman in this dumb society is that you get to complain ceaselessly about your menstrual cycle. I was performing this god-given right at dinner with Mike recently, and my complaints led to more specific complaints about how I don’t like the app that tracks my cycle. Mike—who, whenever faced with a complaint (or really whenever faced with anything), likes to make a game, wager, or project out of it, immediately proposed that he would buy me $25 worth of period apps and I would write about them for this very Lament. I accepted the challenge, secretly thinking it would be easy because the apps were going to essentially all be exactly the same. Tl;dr helpful hint: I was correct.

Like most things aimed at women in our crap society, menstrual apps have not benefited from the same cutting-edge design focus as have apps for men, such as boner apps. On the one hand, sure, it’s great to finally have a way to track your cycle that doesn’t involve manila folders full of weird loose paper and hand-made charts or, worse, charts printed off the internet that have pregnant goddesses and moons on them; on the other hand all these apps seem to be geared toward 10 year olds and make you feel like a fucking idiot whenever you open one of them. This is especially disturbing in the ones that are obviously most intended to help you get pregnant, for you are forced to realize that these apps actually aren’t intended for 10 year olds, and that rather this is the way our cultural consciousness believes grown-ass women ought to be communicated with (emoticons and a vomit-inducing wash of different pinks).

(As an American woman, I am of course totally accustomed to being infantilized. Let us all remember Barbara Ehrenreich’s devastating chapter on breast cancer where she describes getting her diagnosis and then receiving a fun pink gift bag, given to all breast cancer patients, which contained fake diamond jewelry, a pink teddy bear, and a box of pastel crayons. She wonders if men diagnosed with prostate cancer get a blue bag with toy cars in it; it doesn’t seem likely.)

With my $25 gift card, delivered in a tastefully authoritative envelope from Apple including typed instructions about spending the gift card on period apps, I went shopping!

Most of these apps are $1.99, although there are a lot of free ones, and some weird outliers that are really expensive. I bought five for $1.99 and one for $16.99, and I also currently use WomanLog pro, which I believe was $1.99 also, and I’ll throw it in for comparison.

Here is what I want out of a period tracker:

- a place to enter temperature every day, even though I don’t do this right now the cycle day listed on each day in addition to the actual calendar date, so you can see what’s going on in there (your body)

- “night sweats” as a symptom option, which is quite rare as this is mostly a menopause thing and like I said these apps are for kids and people trying to get pregnant

- user-friendly interface or whatever. I don’t want a billion screens to navigate through and “notes” in all kinds of different places

- smart prediction of periods and fertility: my current app asks you to set the length of your cycle and then it doesn’t deviate from that—I want an app that can use all the data you enter to actually predict stuff

- I don’t want any girly cartoon nonsense

- most importantly, I want the symptoms I enter for each day to be readable in some way when I look at the whole month in the calendar. This is hard to explain if you are someone whose cycle is unproblematic, but for those of us who’ve developed crippling late-in-life premenstrual syndrome, it becomes of vital importance to be able to see and track patterns across the month. My current app (WomanLog, which, can I just point out that that is an insane name) just shows the “symptom” icon when you’re in month-view, so if you want to know what symptoms happened on each day you have to go into day view, and it’s impossible to really see patterns easily. I understand this is tricky because the actual size of the calendar is so tiny that filling each day with individuated symptom icons is probably really hard, but I’m just saying, this is the main thing I want an app for.

I chose WomanLog because it is not girly cartoon nonsense—in fact, its color scheme is BLOOD RED, which I appreciate—and it doesn’t rub its emoticon options in your face.

A word on the whole emoticon thing:

The designers of period apps believe that the thing women are most interested in is tracking their “mood.” I think this belief comes from two places:

- the age-old association of women and emotional instability that has led to so much oppression in this modern capitalist nightmare. “The broads surely want to be able to track their insane mood swings and such-like,” says one cigar-chomping period app mogul to another. In my case this is not true, as my mood is as reliable as clockwork: cheerful, then hungry, then stressed out, then asleep. On weekends sometimes add “grouchy” if I am out late and I’m cold.

- The assumption that the ladies love cute little cartoon faces and can have fun comparing and sharing them in the various weird forums these apps make available. Also untrue in my case but perhaps true of the general female zeitgeist at this time, in which case god help us all

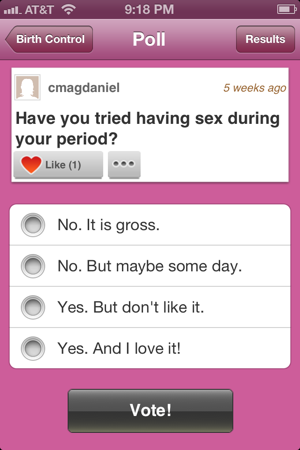

Let me just say right off the bat that every single app I tried comes with an enormous selection of emoticons. See, each day, you choose one of these fun faces to describe how you’re feeling. Many of them are impossibly existential; they also beg the question: if you put the emoticon for “enraged” in your calendar does that mean you were enraged all day? These questions must remain unanswered, alas.

![]()

Another complaint I have is that all of these apps, while giving you a fairly wide array of customizable things you can track, ALL assume you want to track your weight, which I find rude. The idea of weighing myself every day like some prize pig and then entering the number into a tiny judgmental computer is intensely depressing. I get that for some people, tracking weight fluctuations across their cycle would be helpful; I just resent that this is an automatic default thing that every single app makes available.

I’ll run through these apps from worst to best:

Apps That Tell You When To Have Sex If You Want A Boy/Girl:

I did not buy any of these but just wanted to let you know that they exist. My favorite one was called Maybe Baby, which uses an icon of a smiling sperm.

Menstrual Cycle and Sex: $.99

I bought this one without really examining it because I liked how intense and bloody it was. After opening it I realized that this is actually not a period tracker, but rather a compendium of loosely-accurate “information” about sex and periods, and really primarily, about sex on your period. This made me laugh so hard that it was definitely worth the buck I wasted on it.

It includes gems like this:

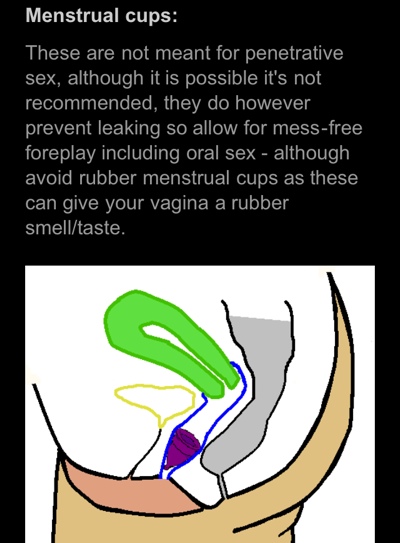

and helpful diagrams like this:

Note: this app is telling you that if you have sex while wearing a Keeper, it will prevent your partner from getting grossed out by your horrible blood. Anyone who has ever worn a Keeper knows how outrageous this is. Unless your partner is not actually penetrating you, OR has a half-inch-long penis or something (which is fine; it’s not the size of the boat it’s the motion of the ocean). Keepers are gigantic and pretty much take up all the room in there. In conclusion, this app rules and I am keeping it forever.

Period Diary: $1.99

Each of these apps makes sure not to display horrifying words like “period” or “menstrual” on their actual icon that appears on your phone, lest a boy see such words and then, having learned that you menstruate, run screaming from you as from a witch or devil. Thus as of right now on my iPhone’s main screen there are all these apps represented by icons of flowers in different shades of pink and other colors soothing to all women, and each one has a mystifying title. This one is called “P.D.” Adding insult to injury, P.D., instead of opening onto a calendar when you click on it, opens onto a fucking GIANT FLOWER, where all your menu options are on individual petals of the flower.

Each of these apps makes sure not to display horrifying words like “period” or “menstrual” on their actual icon that appears on your phone, lest a boy see such words and then, having learned that you menstruate, run screaming from you as from a witch or devil. Thus as of right now on my iPhone’s main screen there are all these apps represented by icons of flowers in different shades of pink and other colors soothing to all women, and each one has a mystifying title. This one is called “P.D.” Adding insult to injury, P.D., instead of opening onto a calendar when you click on it, opens onto a fucking GIANT FLOWER, where all your menu options are on individual petals of the flower.

- calendar itself is okay, but you have to go into a separate screen (i.e. you have to click on a different flower petal) to put in the dates of your period, instead of clicking on the day in the calendar, which is unwieldy

- doesn’t tell you the day of your cycle on each calendar day

- doesn’t do individual symptom icons BUT there is a separate section down below (that changes as you change the date) where symptoms ARE listed, which is perhaps the best that can be hoped for

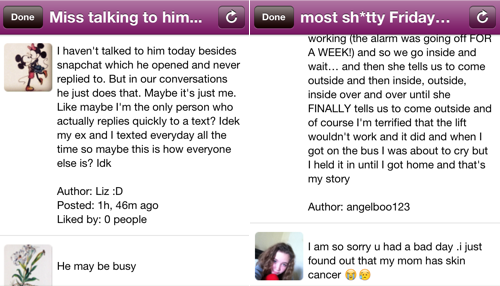

- Like all these apps, P.D. has a “forum” where confused young women talk to each other about boys and whether or not they’re pregnant. One forum I looked at had a closed thread called “AM I FAT” in which the moderator said the thread had had to be shut down because it was filling up with hateful insults.

- No “night sweats” option, so instead I use “crying spells” because the teardrop icon is evocative of my raging cyclical night sweats, which, if you think you’ve ever had sleep disruption problems, fucking think again my friend, as you don’t know what horror is

M Calendar: $1.99

M Calendar: $1.99

- really unwieldy interface:

- to say your period started you have to navigate through TWO additional screens

- doesn’t give night sweats as a symptom; hardly has any symptoms in fact, so I had to write a “note” for each symptom, which means all your info is showing up in all kinds of different places

- calls cervical mucus a “symptom,” which is gross; cervical mucus is beautiful in spite of its dreadful name

- Mood options: happy, sad, sleepy, sick, angry. Pretty much covers it

- The only reason this one didn’t come first (as in, it’s The Worst) is because Period Diary beat it out with its giant stupid fucking flower. One thing you can say about M. Calendar is that there are no flowers in sight.

Pink Pad: $1.99

Pink Pad: $1.99

- shows up in dock as “pink pad,” so boys won’t know you are a menstruating adult but they will think you are a goddamn baby

- makes clicking noises when you navigate around in it, which I might like but I’m not sure

- on the calendar, you can see IF there’s a symptom listed on a given day, but there’s no indication of which one, so to find out you have to go to a different view and read your month as a list, which is utterly confusing and useless for seeing monthly patterns

- no “night sweats” option, so I use “hot flashes”

- has a horrible forum where teen girls ask each other if it’s weird their boyfriend didn’t text them back yet

M&O Calendar Premium: $16.99

Okay, so this one, which cost a whopping seventeen bones or clams, should be the real Mercedes Benz of period apps, right? That is a HEFTY price. Maybe I just didn’t use it for long enough, but I have to say that this price is utterly non-reflective of the quality of this app. Alas.

PROS:

PROS:

- has the decency to show up on your dock as just a calendar icon instead of a flower or a baby’s face

- doesn’t have a forum!!!

- Is not cutesy at all

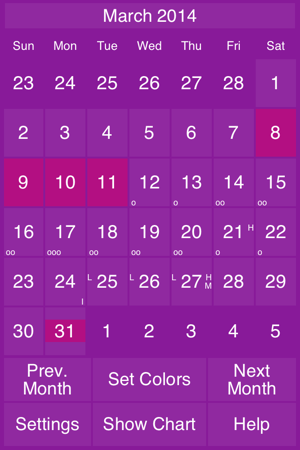

- Does put individual symptom icons on each day. Unfortunately though they aren’t icons but LETTERS you assign to each thing you want to monitor. So on a day when you had cramping and a night sweat, it will put a “N” and a “C” in different corners of the date. Adding to the confusion, you also rate each symptom as “mild,” “medium,” or “high,” so next to each letter indicating a symptom they also put a letter indicating the severity. So in one day on your calendar you might have “NM” and “CH.” This is pretty confusing but I guess you could make yourself read it fluently

CONS:

- VERY hard to read. Undifferentiated color scheme of purple. Very confusing icons:

- I don’t know if you know how the female body works, but basically a few days after your period you start moving toward ovulation, as your body prepares to pitch yet another egg down into an ovary in the hopes of getting pregnant. As you get closer to the actual day of ovulation, your odds of getting pregnant get higher and higher. Your cervix comes down lower in your body and the opening gets bigger; your start producing more and more “cervical mucus,” which I’m sorry that’s such a horrible phrase but that’s what it’s called; your body temperature starts rising. So my point is that all of these apps chart your supposed “fertile days” along with your period. Some of them, inexcusably, depict this phase of your cycle with a little icon of a flower that gains petals as you get closer to ovulating and then loses petals as you move past ovulation and your egg slowly dies inside of you; another missed opportunity to become a fully functioning human being, alas.

- So anyway, M&O Calendar depicts this fertile phase as a series of circles: one circle on the first couple days; two circles; then three circles for when you should ovulate. Needless to say this is incredibly confusing, visually. The other apps either use a flower, which is dumb but easy to read, or a different color shade to differentiate your fertile days from your infertile days (WomanLog just puts one symbol in the corner of each of your fertile days)

I Period: $1.99

I Period: $1.99

I don’t know why this is called “I Period” but not only do I LOVE that name, it is also the BEST ONE. It’s so good in fact that I’m going to switch from my trusty ol’ WomanLog. News flash: I Period has SOLVED the “individual symptom icon in each calendar day” dilemma! Plus it looks good, is easy to use, and doesn’t give you any bullshit cartoon flower nonsense. It even gives you the day of your cycle in the section underneath the calendar, for each calendar day, which isn’t ideal (WomanLog still is the winner in this regard, with a small cycle-day number NEXT TO the calendar date in each day-slot (god that is confusing to type), but all things considered, I can settle for this one.

General conclusions:

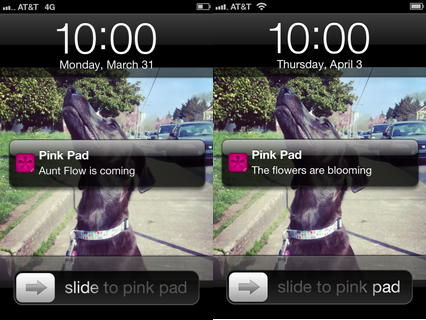

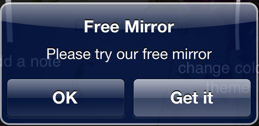

After signing up with all these apps I started getting tons of notifications that my period was coming. Some of them are fucking insufferable:

I also got notifications for drinking water, and for helpful add-ons like this:

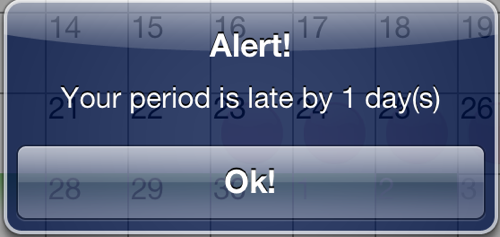

Because my cycle currently is all fucked up, I also have been getting notifications like this:

which if I weren’t so beautifully in touch with my body and so blissfully uptight about birth control, would actually be terrifying. Imagine being a 16-year old and getting a pop-up notification like this.

Plus, in light of the cutesy way these apps all try to hide what they really are so that boys won’t know you have a period app, I have to say that a giant “YOUR PERIOD IS LATE” message appearing on your phone is surely significantly more embarrassing than someone seeing a tasteful “period calendar” on your dock.

Period Euphemisms: Why are they? As a rule, we are so uptight about saying “period” or about letting anyone know we have a tampon in our purse. There is a whole huge market for ingenious bags and boxes and envelopes that you can have a tampon in without anyone knowing, and period euphemisms are as time-honored as cherry pie (sorry). From the gross “Aunt Flo is visiting” to the enigmatic “I got my dot,” Americans have found many delightful ways to avoid saying “I AM MENSTRUATING,” which is in keeping with our national pasttime of just giving uncomfortable things inoffensive names in the belief that this makes the uncomfortable thing go away.

Additional advice to Mike for making his period app:

One thing all of these apps lack is COMPUTING POWER. This is where I think you could actually make a huge difference. So in each of these apps you can enter all kinds of information for tracking purposes, but the app itself doesn’t USE your information. You can tell it about your cervical mucus and your body temperature and that you’re feeling horny, but it doesn’t make predictions based on this info. As far as I can tell, all these apps just use PURE MATH to calculate the dates of your period and your ovulation, whereas in a real human body, all these other indicators are much much more reliable. I wonder if an app could be powerful enough to take into account your night sweats, your mood, your temperature, etc., and be like “oh actually here is when you will ovulate probably.”

Future Exchange: RoboCop

From the atom bomb to the Hoverboard®, Science Fiction’s supernatural prescience in the realm of technological innovation is exceedingly well-documented—real world science increasingly intertwines with its imaginary counterpart in bizarre and uncanny ways. By contrast, the ways in which Sci-Fi portrays its speculative economic systems—though no less significant—have received considerably less scrutiny. In the new feature Futures Exchange, Zuckerberg’s Lament publisher K. Mike Merrill invites a re-examination of these imagined economies: a critical look at Science Fiction Cinema’s portrayal of finance.

RoboCop

Paul Verhoeven’s original Robocop is a cynical, curiously revered 1987 film about a police officer who is also a robot. It’s also in some ways the Platonic ideal for what Futures Exchange hopes to explore in our semi-regular communiqués: a Science Fiction film whose fundamental conflict hinges on the social and political consequences of economic policy.

A movie often recognized for its prophetic portrayal of Detroit’s swift, dystopian decline (something that anyone paying attention to the city’s significant white flight at the time might have envisioned), the first Robocop’s apocalyptic socio-economic predictions were only magnified in its sequel — in which derelict Detroit hangs unthinkably on the precipice of bankruptcy. This is the kind of shit that we live for: cinema that suggests radical civil and societal revelations through economic policy — policy that by some unimaginable twist of fate finds itself tested in real life, in real time.

In the 2014 of our collective imagining, it’s telling that the idea of a superhuman bionic policeman seems somehow a hell of a lot less fantastic than that of a major international tech corporation headquartered in downtown Detroit. Set scarcely fourteen years in the future, one of the strangest things about this year’s Robocop reboot is how totally tone-deaf it manages to be about the plight of contemporary Detroit — significantly less conscious than Verhoeven’s was over a quarter century before it all actually happened. The new Robocop’s Detroit has somehow seemingly emerged from its current financial ruin, with few signs of the previous decade’s pockmarks. It’s a Detroit that appears in considerably better shape than both the Detroit of the original film and the Detroit of present day — an astonishing windfall that’s never addressed directly.

The one piece of evidence we’re given for Detroit’s economic recovery comes in the form of OmniCorp — a forward-thinking multinational with major defense money that seems not only to be shouldering the tax burden of an otherwise insolvent city, but also voluntarily field test their one-of-a-kind, two billion dollar investment in its corrupt and lawless streets. Lead by CEO Raymond Sellars (played sympathetically by Michael Keaton), OmniCorp’s noble mission is to remove the human cost from defense and law enforcement — replacing flesh and blood soldiers with mechanized, completely objective automatons. Though already successfully helping to police nations throughout the rest of the world, the U.S.’s bowtied, big government luddites uphold legislation that still ascribes value to subjective reasoning and the fallacy of free will — leaving American citizens in the regulatory lurch.

Sellars is an archetypical Silicon Valley Libertarian — riding an ever-cresting wave of progress, and fighting the good fight against the prohibitive powers-that-be and their inanely regressive policies. In an effort to fast-track the inevitable shift in social tides, Sellars deftly proposes a hybridization of man and machine — an undertaking that costs him a literal fortune in bionics, dramatically improves the well being of the city’s populace, and saves the life of an otherwise doomed Detroit police officer. (It’s important to note that R&D for this project takes place in China, presumably out of reach of the meddling American government.) What do the filmmakers assign him for his efforts, besides a triptych of Francis Bacons in his office? He’s villainized for cybernetically bypassing one dude’s freedom of choice — a dude who would be otherwise dead without him.

Robocop 2014’s intended moral appears to be that the civil liberties of the half-dead few outweight the well being of the many. The objective viewer can clearly access a great deal of merit in OmniCorp’s business stratagem — of financial and social advantage to both its progressive corporate architects and society as a whole. The film miscasts the company as a strawman for the Obama Administration’s drone strike policies, when in reality what they propose is a discriminating, impartial, and mutually beneficial solution to the many failures of the human condition.

The film’s greater failure is that in its heavy-handed attempt to pin the story to a political agenda, it ignores a perfectly fascinating reality just under its nose: the very real contemporary dystopia of Detroit itself.